On the Boundary Crossing in Maryn Varbanov’s Art Practice

It has been two decades since Mr. Varbanov passed away. Two decades is not a short period of time, yet it seems it was only yesterday that I was working with him. Back then we gathered around Mr. Varbanov, our hearts filled with endless expectations of contemporary art. We were indeed like a tabula rasa with our supplicants’ hearts, anxiously anticipating enlightenment from Mr. Varbanov. Our startled eyes scanned his every draft, the sight of which filled us with excitement as well as anxiety. We could discern, however vaguely, that a new era was dawning upon us. Today, after two decades, when we revisit these drafts and Mr. Varbanov’s art thinking, we are still astounded to find that his unrealized exhibition scheme still strikes one as experimental; what he had envisioned almost two decades ago is exactly what we are practicing and discussing today.

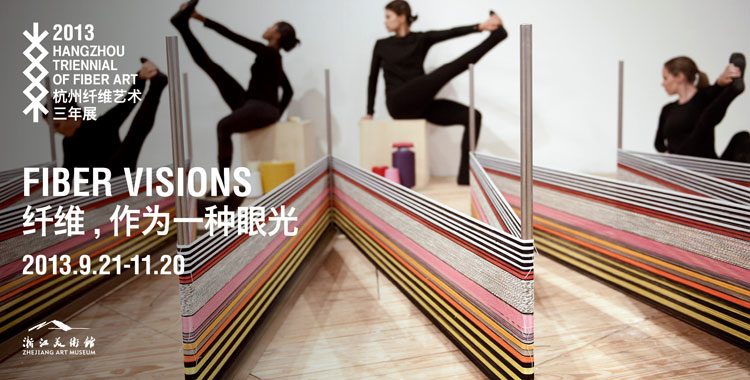

Since last year, we have been planning commemorative activities to mark the second decade since his passing. Last year, we successively held exhibitions and symposia in Shenzhen, Shanghai, and Hangzhou, both to pay homage to him and to survey his artistic philosophy, ideas and ideals in order to provide fundamental motivation for our further evolution as artists, especially with Maryn Varbanov and the Chinese Avant-Garde in the 1980s: An Archival and Educational Exhibition. Working on an exhibition with this in mind, I think the whole process was one of revisiting his art and thinking, and of improving the quality of our own thinking and cognitive efforts. It was also intended as an act of homage to Mr. Varbanov. This retrospective has now made me more acutely aware that Varbanov’s life was one of constant exploration, and his boundary-crossing trails imbued his artistic practice with a broad and challenging outlook. He was always one who crossed boundaries.

The Charm of Kesi (K’o-ssu)

At the beginning of our course in tapestry art with Mr. Varbanov, he told us that the Chinese craft of K’o-ssu had exerted an influence on contemporary tapestry art in Europe. When he studied at the China Academy of Art in the 1950s, he majored in oil painting before switching to dyeing and weaving at the postgraduate level. During this period, he came across the Chinese art of K’o-ssu and found it very appealing. He believed that the K’o-ssu of the Southern Song had already gone beyond the replication of rough copies and attained the excellence of re-creation. Recently, when we were preparing his notebooks, we noticed the following paragraph: “One of the many inventions created by ancient Chinese civilization is the classical weaving technique,“K’o-ssu”. The ancient Chinese weaved with a magic hand, thread-by-thread, in a fascinating mathematical order that could compete with any digital brain today. This ancient art of tapestry caught the eye and moved the heart with such miraculous images and created by a sheen of silk and the balanced perfection of a spectral cosmic rhythm.”

The exquisite K’o-ssu technology and its vibrant expressiveness had placed Varbanov under its spell. European tapestry is also woven with warp and weft threads. An art form of great importance, tapestry became popular in France and Southern Germany in the 14th century, with Biblical stories, historical tales and myths as its main themes. European society had been dominated by the Church, and until the 17th century the art of tapestry was held in higher regard than painting and sculpture. In China around the same time, a tapestry art totally woven by hand and based on warp and weft threads was developing in parallel with its counterpart in the West, the only differences between them being the materials used (silk versus wool). Mr. Varbanov’s chance encounter with Jean Lurçat’s small-scale tapestry exhibition prompted him to switch from painting to tapestry, as the exquisite craftsmanship of tapestry art in both East and West swept him away. This was the first boundary he crossed.

In 1959, Varbanov returned to Bulgaria after completing his studies in China, and founded the Department of Textiles at the National Academy of Art in Sofia in an attempt to combine innovation with regeneration. He installed a loom he had designed in his home and devoted himself to work. The structure, material, color, texture, and all that happens on the loom inspired his sensitivity and creativity. During this period, Varbanov was more concerned with the purity of the language of weaving, and his enthusiasm and pertinacity were evident in his quest to perfect the self-expression of tapestry as an independent art form. His dedicated research in China, as well as the excavation and rejuvenation of the Eastern European weaving tradition after his return home, not only perfected his exquisite craftsmanship and techniques, but also brought to fruition his efforts to possess the heritage of the art of tapestry in an innovative and visionary way. This was best evidenced by the unique artistry he demonstrated in the innovation movement in tapestry in the 1960s and 1970s.

Breaking the Barriers

The 1960s and 1970s were exciting times, when an avant-garde movement devoted to “Total Art” pushed the traditional art of tapestry to the foreground of the conceptual movement that “sought the reconciliation of life and art in an attempt to build a living environment for the new age”. The “warm” decorative parts in the traditional architectural realm of tapestry were dutifully subjected to innovation of the most vibrant kind in this campaign to build a new living environment. During this period, Varbanov and his contemporaries championed modern tapestry. On the one hand, they succeeded in breaking down the conventional barriers between art and craft, thus altering the previous set-up characterized by the antagonism between artists’ drafts and craftsmen’s techniques. Equipped with concepts furnished by the new living environment, they daringly cut the umbilical cord between modern tapestry and traditional craftsmanship, and exerted innovative control over the entire creative process. On the other hand, they tried to make the two-dimensional weft and warp threads stand erect, so that the tapestry could stand alone without the support of the wall, thus plunging further into space as a form of soft sculpture. There it attempts to find expression in a form of existence that is interdependent with modern architecture. The soft texture particular to fiber material and its affinity with nature allow its unique warmth to shine through the modern constructed environment characterized by reinforcing steel, cement, and glass. In the meantime, the soft quality and malleability of fiber material also make it possible for tapestry to adapt readily to the rich and ever-changing realm of modern architecture, becoming an integral part of it. In this movement dedicated to the construction of a living environment for the new age, Varbanov soberly pointed out, “tapestry art combines the richness and freedom enabled by modern architecture and also addresses those caveats against it being cold and mechanistic. It aims at restoring the psychological exchanges between man and nature, bringing back human warmth, and constructing the living space that is really needed by modern man. Soft sculpture comes with a unique formal language of its own, and the appropriate means to connect with modern architecture”.

During that period, he introduced the traditional formal language of weaving to the gargantuan modernist space and brought malleable plasticity into the hard modern space, thus creating a series of monumental works. Here the independence of “soft sculpture” was accentuated, and through improvements on itself and the crucial role it played in the formation of an environment was also highlighted as never before. Tapestry, an art form with its primeval decorativeness and functionality, thus completed the transformation from the two-dimensional into the three-dimensional, into the spatial, the malleable, the free creation based on the combination of material and form, all within the free space of modern architecture. It ultimately achieved the status of a new, experimental and spatial art form. And for Mr. Varbanov himself, this was also crossing a boundary in his art practice, whereby he turned away from a nomadic, somewhat disoriented scholarly experience and returned to and went beyond traditional formal language. It was the trend of the time, and he was one of the trend setters. At the height of Lausanne, Varbanov became one of its leading figures.

Concentrated Efforts

The expanding influence of modernist culture and thought also prompted the art of tapestry to complete the transformation from being a part of traditional culture to being a constituent of modern culture. The transmission, fusion and evolution of traditions have made artists realize that various materials in fiber art can be employed in experiments that challenge the norm, in order for a brand-new, sculptural language to develop. The revolutionary use of this language of materials was to fundamentally break with the conceptual shackles in traditional art forms which held materials subordinate, and thus deepened the artist’s conceptual and formal grasp of modern tapestry, which in turn prompted the artist to explore and experiment extensively with the unique language of fiber art. For Varbanov, tapestry was not simply a craft art. He began working on tapestry by positing it as a plastic art with a sense of purpose. Although on the surface he seemed to be repeating an ancient artistic language, in reality he was determined to identify new implications relevant to our times in the ancient language of tapestry.

During this period, Mr. Varbanov experimented variously with the form and material of tapestry. Thanks to his rigorous groundwork training in sculpture and painting, he developed an extremely acute awareness of the plasticity of form and the relations between works of art and the spaces they inhabit. He realized that the softness of tapestry and the malleability of its form provided huge potential. In his creative output from the years 1969 and 1970, Varbanov showed some early signs of soft sculpture tendencies. He made use of the heftiness of linen and woolen materials, and the interlacing structure of fiber weaving, in the formation of soft sculpture works marked by the extremely robust and novel use of round and semi-round carving. In 1969 he completed Aporia and his 1970 work Composition 2001 was hung midair ( exhibited at 5th and 6th International Biennale of Tapestry, Lausanne), and in the mid 1970s he created the large-scale work Column Series at the Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris, which was no doubt a perfected interpretation of the use of space by soft sculpture.

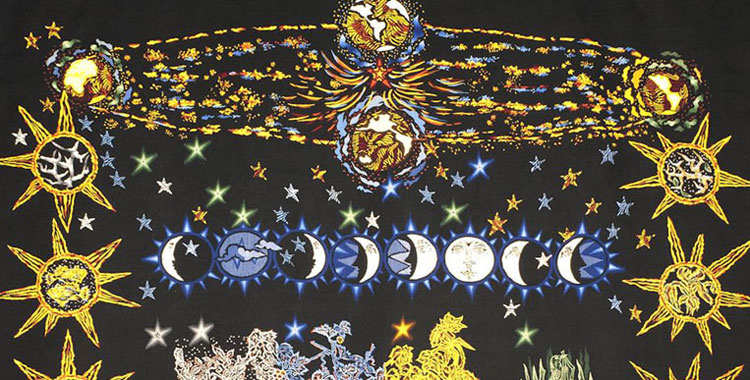

Varbanov plunged into the “epic” era of the modern art of weaving without hesitation, and the materials were the first language of his grand poetic imagination. Exploring the various possibilities of the expressiveness of fiber materials themselves also constituted an important part of Varbanov’s crucial practice in this period. He applied to his tapestry those traditional methods of treating goat’s wool still in practice in rural Bulgaria. As goat’s wool was a particularly difficult material in terms of treatment, Varbanov would rinse finished tapestries under a high-pressure tap, so that the centrifugal movement of water would render the quality of the wool more tangible. He sought to unlock the treasure trove of folk craft art, and his earthly warmth seemed to have an affinity with the feel of natural fiber. He loved natural materials such as wool, linen and cotton just as he loved the wild patches of green and the flocks of sheep in the Oriahovo. His works Koziac, Festival in Rhodopes, Autumn of Rhodopes and Rhodopes Mountains from the late 1970s were all made with goat’s wool and carried the stamp of the unique Varbanov style of stimulating multiple perceptions from the visual and the tactile to the other senses. Varbanov excelled in the use of natural qualities of the material in the explorative-creative process, and in doing so managed to break the mode of traditional weaving and create a versatile approach to weaving and styling. I really enjoyed his Byzantine and Orphee Series from the 1970s, where the exquisite techniques of weaving were preserved to the utmost: the subtle shifts and turns in stitches, the palimpsest of sense and sensibility in the structure of the imagery, as well as the noble and elegant touch in the richly exotic colors. Varbanov’s immersion in the realm of weaving opened up the secrets of tapestry, and created a new art form for contemporary fiber art and the various new possibilities it promised.

It is worthy of note that these materials and stylistic and color elements were imbued with profound thinking by Varbanov: “I am intrigued by the emotive and aesthetic qualities of material. Man exists in time and space, and I pray that the physicality of tapestry, derived from and predicated on the multitude of meanings of the ontological spirit, will remain instant and perpetual at once”. “The charm of the natural colors of woolen threads and their mysterious influence lie in their natural existence and, at the same time, in the astonishment that nature incurred in our inner world of emotions and thoughts”. Varbanov explored deep into the materiality of the “thing” itself with great effort, so that he could contact the individual spiritual experience, and the sense of symbiosis of man and the world, in order to extend constantly the boundaries of the plastic arts. Varbanov had become a real artist through his efforts to reconstruct the meaning of plastic arts at a time when conceptual breakthroughs were constantly took place.

New Boundary Crossings

Varbanov’s explorations and achievements were rewarded with invitations to visit and do creative and research work at studios in France and Australia in the 1970s. In 1986, he was invited by the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts (now China Academy of Art) to Hangzhou, the ancient capital where the Chinese art of K’o-ssu flourished. He returned to his home away from home with the view to establishing an “oriental tapestry art center” in China. Luckily I was among the first group of students taught by Mr. Varbanov. Back then, he guided us young artists in the reinterpretation of traditional Chinese elements, seeing it as the medium of conveying the “image” in the exploration of possibilities of merging the artistic languages of East and West, so that new elements could form a type of groundwork for the reconstruction of contemporary art. He inspired our enthusiasm for the resources furnished by our own culture, and pointed us to ways to conduct the archaeology of knowledge of such Chinese elements as hieroglyphs, bronze, shadow puppetry, and Dunhuang frescos, with an aim to explore the contemporary relevance of these charming traditional themes, so they could be transformed into creative resources serving the needs of contemporary art. He demanded that we focus on locally available materials, such as silk, linen, and coir, and he was emphatic about the original, unspoiled state of materials, the craftsmanship of works of art, as well as their being in situ. A foreign artist, he nevertheless helped us unlock the treasure trove of our own artistic tradition, and readily initiated us into the society of boundary crossers as an experienced, confident elder. The guiding principles of Varbanov reflected an approach characterized by reconstructing culture from its roots. From June to September 1986, Mr. Varbanov led us in our in-depth explorations of our own unique traditional culture, and completed nine pieces for selection by the International Biennale for Tapestry (Biennale Internationale De La Tapisserie) in Lausanne, Switzerland, three of which were eventually selected. These three pieces attracted a lot of attention with their broad orientation and a manifestation of Chinese culture’s spiritual dimension, as well as their regionalism and craftsmanship.

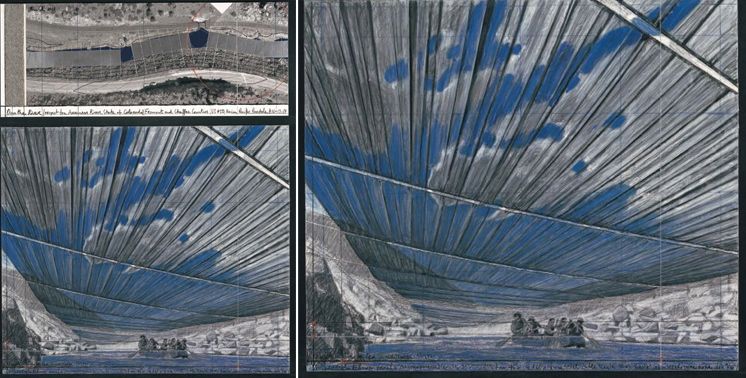

Varbanov’s teaching and creative work at Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts announced a kind of experimentalism in art characterized by audacious boundary crossing, so much so that we cannot simply call those works tapestry, but rather view them as the first ebb and flow of contemporary Chinese experimental art within academia that attempts to return to the fountainhead of life for “meta-creation”. The Lausanne Biennale should also be seen as the debut of contemporary Chinese experimental art as a whole on the international stage. While guiding us in the experimental crossing of boundaries in contemporary art, Mr. Varbanov’s own experimentalism seemed to undergo rejuvenation: he started to cross boundaries by constructing a new formal language for fiber art. At this time he started with his extraordinary sensitivity to contemporary life and society itself, to the language and material of urban life, in an attempt to achieve breakthroughs in the new consumer materials of urban life. In 1988, he started to plan for his own personal exhibition. During that period he drafted a lot of sketches which differed from his earlier, effortless renderings of “soft sculpture”, with their assertive spatial framework that emanates an urban, installation effect. In these impressions of large-scale installations, we notice an intense conflict between form and concept; immersed in the soft mesh structure were postindustrial steel chains, pipes, and hammers. Varbanov intentionally strengthened the tension between these conflicting materials in order to form a massive sense of space and time. Here he attempted to explore a new visual sensitivity with the conditions and conflicts of industrial societies.

While leading Chinese artists with a variety of experience in their quest to cross the boundaries of the already existing art forms through revolutionary experiments with tapestry, Varbanov himself also plunged into new realms of boundary crossing. He seemed to be taking stock of his works through the explorations of Chinese artists and, in the meantime, gained the momentum for another strike. In this boundary crossing, Varbanov found himself in a purely cosmopolitan space, transcending the “harmony” of classical reason and entering the conflicts of contemporary life, directly confronted by the intensity of these conflicts. In this way he was focusing on existential dilemmas and the fundamental concerns of human existence. These sketches displayed a force hitherto unseen, an architectonic energy fully in control of space. It was a pity that he was not allowed enough time to complete his program, otherwise the boundary crossing would not have remained one “on paper”, but rather one that could transform the entire setting of creative art in the public space of our time.

In the meantime, Varbanov was mulling over an even bigger “boundary crossing” project. From the materials unearthed for this documentary exhibition, we noticed a six-year plan he drafted for the tapestry research center, in which he studied the production and expansion of tapestry art from the perspectives of creation, research, as well as experimentation (i.e., the model that combines production, learning, and research that we so often talk about today), and this was a model marked by real boundary crossing in spiritual terms. On the one hand, he fully acknowledged the importance of research and experimentation in artistic creation, and viewed this constant quest as the core of a model, as a particular constancy in the process of development. On the other hand, he was also fully aware of the significance of promotion and industrial support for creative experiments. In short, Varbanov designed a sustainable model for art in the context of society at large.

Maryn Varbanov’s entire life was replete with creative thinking, with boundary crossing and siege breaking. Today when we revisit his sketches and models, we are constantly rewarded with discoveries of the revolutionary concepts and prophetic judgments latent in his work. Maybe in every creative act of ours with a hint of boundary crossing, we could always detect a trace of him as the master boundary crosser. Mr. Varbanov will remain our guide and mentor forever.

Shi Hui

Director of Varbanov Tapestry Research Centre and Fiber and Space Art Studio, Department of Sculpture, China Academy of Art