Objectives

Examining traditions

In the history of human culture, there has never been a cultural form that has such a long history as textile practices and fiber art.

Textiles, thread, fibre, cloth, and fabric – at once commonplace and indispensable – attracts a wide array of myth and metaphor. Its flimsiness suggests the precariousness of human existence where life can hang by a thread. It also makes connections through stitching disparate entities together, so in Hindu cosmology a sutra or thread links the material and spiritual realms. Because it is pliable, thread can trace complex structures both literally and metaphorically. One may thread one’s way through a maze or through a series of conflicting arguments. The word clue originally meant a ball of yarn, so narrative is readily compared to a thread drawing readers into a text and holding them there. Its ability both to trace structures and to create them by criss-crossing on the loom means that thread figures in many myths of origin. We are wrapped in cloth at birth and swaddled in at death.

The knots used by our ancestors to record what happened in their lives could be considered the earliest attempts at the construction of interlaced structure with flax material.

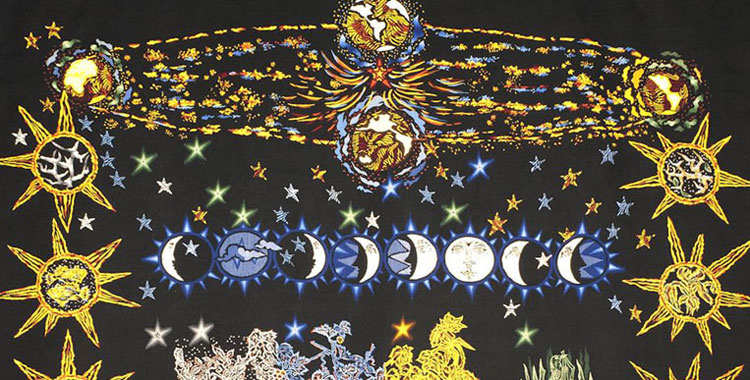

In China silk materials were discovered that dated back to the later stages of the Neolithic Age. In 1958, pieces of thin silk were discovered at the lower cultural strata of the Qiansanyang Neolithic Site at the southern suburbs of Huzhou in Zhejiang Province. They were identified as belonging to the Liangzhu culture dated 4,700 years ago and certifiably the earliest known silk textile products ever discovered in the world. Ke si technology employing weft and warp yarns were developed in the Tang and reached its apex in the Song. In the Southern Song capital of Lin’an (i.e. the Prefecture of Hangzhou), Ke si art with Song Dynasty landscape painting as its basis was able to fully exploit the unique weaving techniques of the time and perhaps even outperformed the originals in terms of vividness and colouring, earning their rightful place as a treasure in Chinese textile art.

In France, ‘Gobelin’, is known as classical tapestry. It is generally a figurative form, which tells stories about human life. As such tapestry is a narrative art. The Bauhaus and in particular Anni Albers played a very positive role in the promotion of textile art. Jean Lurçat is regarded as someone who promoted and revived French modern tapestry as an art form as well as establishing workshops for production and industry. In 1962, Lurçat, together with the government of Lausanne, Musée cantonal d'Archéologie et d'Histoire, and the French Ministry of Culture, launched the Centre International de la Tapisserie, a two yearly tapestry exhibition held in Lausanne. The International Center of Tapestry Ancient and Modern (ICAMT) in Lausanne, and the world’s first ever International Biennale for Tapestry created a stage for modern fibre art.

The first Biennial took place in the summer of 1962 and showed classical tapestries representing 17 countries. From 1965, the Biennials included a range of work far beyond the original definition of tapestry to include embroidery, stitch, appliqué, collage, macramé, knitting, print, photographic montage, mixed media, soft sculpture, found objects, installation, environmental pieces, performance based work in many different materials, fibre and techniques. During the late 1970s and 1980s the Biennial saw a shift of dominance from East European works and ‘loom thinking’, working directly with fibre and material without a prepared cartoon or drawing for classical tapestry work, to areas of the world whose schools of textile art, together with commissioning possibilities for art in public places, had been fostered. This is why the works from China Academy of Art in 1987 made such a big impact. The scale of the Lausanne exhibits were set at between 4 and 12 square metres to ensure historic connections between mural scale work within an architectural context for public participation.

The international tapestry biennials of Lausanne became the singular and most worlds renowned for presenting experimental work on a global stage. During the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s the Biennials turned Lausanne into a world centre of fibre art. In the 21st century we are able to see more of some examples form at international art events such as the Venice Biennale and Documenta Kassel.

In the late 20th and 21st centuries globalisation, the Internet and rapid urbanisation have all had an impact on how we think of social space so the relationship between virtual and physical space is a challenging one.

The questions now are;

How do we discover creativity in the social, which reveal Chinese characteristics?

How do we highlight the significance of creative culture?

How do we think about spirituality in a world where conspicuous consumption dominates?

How do we bring together a history of the future to create an era of prosperous symbiosis of art, life and industry?

Within the histories of fibre art we can discover the creativity, spirituality and imagination. Contemporary society is undergoing rapid transformation. China leads the way and offers a rich soil for artistic creation. The material genes in the digital age can also facilitate and combine with renewed fermentation.

Our task and contribution is to re-examine and re-activate tradition, and cultural heritage in order that the nutrients of contemporary life once again turn artistic creativity in the form of fibre art questioning people’s renewed understanding of physical space and time in the digital era.

Hand · Mind

Showcase Craftsmanship, Create Tools for Thinking

A strong tendency of recent years is to regard technology itself as the driver for both wealth creation and cultural change. By contrast we want to focus on the everyday level of world formation our shared ways of making sense of things through the experience of making things. Craftsmanship was closely linked to manual labour and also carried crystallised thought. Every good craftsman conducts a dialogue between concrete practices and thinking and this dialogue evolves into sustaining habits, and these habits establish a rhythm between problem solving and problem finding. The ability to enter this dialogue, to find the rhythm of involvement with the materials, is slow to develop. It requires both long practice and regular communication with others who have ‘mastered’ the craft. And while techniques do evolve, the pace of change within a craft tends to be slow. This is not a defect as the slowness of craft time serves as a source of satisfaction; practice beds in, making the skill one’s own. Slow craft time also enables the work of reflection and imagination—which the push for quick results cannot.

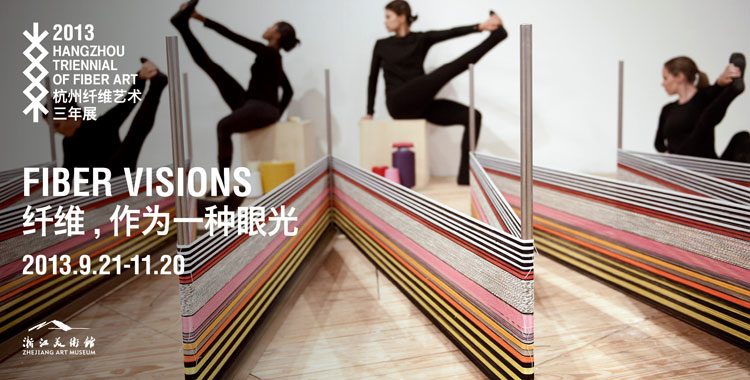

In the move from textile to fibre art, one of the oldest crafts ever, unique forms and linguistic expression can be richly detected. Fibre art employs natural, manmade, chemical and synthetic fibres in its creation of special meaning and strong visual impact by way of weaving, knitting, lacing, winding, spinning, sewing, embroidering, binding, dyeing and gluing. Its rich artistic language and communication in a plethora of forms within exhibition space cannot be matched by any other art form.

In the Greek epic Odyssey, Odysseus’s wife, Penelope, is depicted as a great weaver. Her name contains ‘weft’, suggesting her identity as a cunning weaver. According to the Homeric epic, when faced with many suitors with unfathomable intentions, Penelope the faithful and wise wife comes up with the trick of ‘weaving a burial shroud’, promising the suitors that she would marry one of them once the shroud is completed. By day she weaves and by night she undoes part of the shroud, and this repetitive deconstruction and reconstruction are but deferral in waiting. In the story of Penelope, the shuttle as a metaphor for time already reveals the power of weaving in terms of accumulation and anticipation. The final product of such weaving is hence uniquely touching.

Creating a spiritual ideal through craft poses a challenge to the social culture of our day. It demonstrates the artist’s humanistic concerns and reflections on the culture of our future in the historical context of post-industrialism.

Pioneering heritage

Renew Academic Discourse and Open Up Innovate Areas

The contemporary is not a style or a fashion. Contemporary art comes with an uncompromising critical spirit, which constitutes the core of contemporaneity. Contemporaneity has to do with the temporal implications of a globalised, technologicalised, urbanised and informationalised society, and it is the profound root cause of the cultural transformations and innovations of our day. Fibre art has evolved from traditional manual and machine weaving to industrialised weaving and finally to digital weaving, with the increasingly diversified use of new material and new technology. Its experimental nature with the kind of creativity associated with our era has prompted it to form a close relation with contemporary culture. Fibre art has multiple connections to human life, urban development and the optimisation of living environment, thus becoming a very important reflection on contemporary art. It embodies the critical and creative inclinations regarding urban development and objectification. While focusing on creation, it also critiques human understanding of the object and the questioning of the objectification of humanity, the judgments on objectification as well as reflects on urban consumerism.

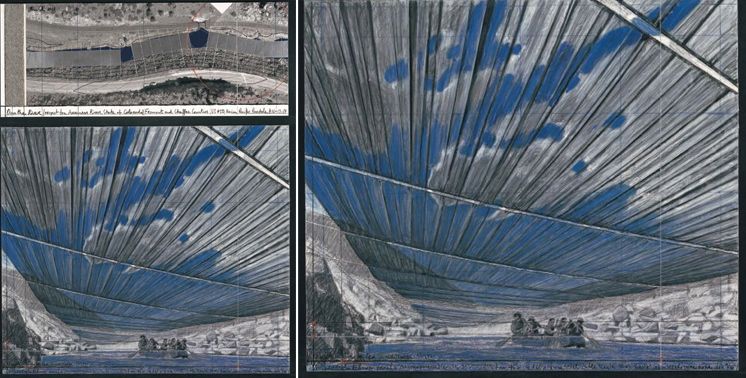

Fibre art is embedded in, humanity and nature. Creating with natural or artificial fibre material poses new challenges to our social environment today. From the art of weaving in the age of graphic design, via the soft sculpture in the era of cubism and expressionism, to installation art in the age of space construction and floated art that aims to conquer space of large dimensions, fibre art has continuously demonstrated new vibrancy with the changes in the spaces of human social life. In the urban space characterised by steel and concrete jungles, we often feel that natural warmth is missing and hence nurse a nostalgia for an agrarian society and harmony between man and nature. Our age has afforded us opportunities for new public art. Our major task is to find out how we can break free of old confinements in the context of digitalisation and globalisation and point to the common issues of the world, so that we could construct a new cultural language and increase the creative potential latent in fibre art.

Local·Global

Deepen Local Concerns and Build up International Impact

History and age have afforded us fresh opportunities. Modern fibre art has become the continuously developing art genre in terms of material and medium that perfectly embodies the Zeitgeist. Many countries have resorted to fibre art creation in order to demonstrate the advanced levels of national art development. The rapid growth of the Chinese economy has laid firm economic foundations for us. The history and reality of local textile industry has supplied us with causes and motivation. We should particularly ask ourselves the question how China, as a textile superpower with a longstanding tradition, can reconstruct new local concerns by drawing upon emerging small to medium markets and the rapid urbanisation process for its vitality and motivation, as we try to deepen our local concerns. The Hangzhou International Triennial of Fibre Art project will deploy the local resources and cultural heritage of Hangzhou, Zhejiang and by extension the entire Yangtze River Delta in an attempt to have more say in cultural matters in the new age. It will be committed to discussions of the contemporaneity and creative potentials of fibre art from new perspectives, and explorations in fibre art’s humanistic value and implications for the future. It will lead contemporary fibre art, industries, commerce and fashion in an attempt to recreate a local apex and international standing.

The first Hangzhou International Triennial of Fibre Art will be an open art dialogue between artists, art lovers and people all of whom connect with time, history and the city. It will promote the union between urban creative industries and new rural culture. While raising the city’s profile and putting in place an industrial platform, it also will push Hangzhou, Zhejiang, and the academic, industrial and textile professions to collaborate in the construction of a three-dimensional cultural platform. The first Hangzhou International Triennial of Fibre Art will be a new coordinate in the contemporary fibre art forum worldwide. Its continuous development will create a cultural focus internationally. In the meantime, this international exhibition will facilitate the further development of a cultural powerhouse in Zhejiang at a high level. It will raise the international profile and influence of Hangzhou and Zhejiang in terms of cultural and economic development. The first Hangzhou International Triennial of Fibre Art will play a leading role in the development of contemporary fibre art with its artistic practice and theoretical research, turning Hangzhou into the Oriental centre of fibre art, so that the International Triennial of Fibre Art will be an international art extravaganza with both a local, Asian focus and international standing.